Beyond Borders

How U-M's Program in Chemical Biology allows students to transcend traditional barriers between colleges, departments and disciplines

For years, researchers have pursued biology in chemistry labs and chemistry in biology labs — but chemical biology didn’t emerge as its own area until relatively recently.

Far from being a household term, even the journal Nature Chemical Biology felt the need to do a bit of navel-gazing in its 10th anniversary issue last year, pondering in an editorial whether chemical biology had yet “achieved a distinct identity” while soliciting definitions of the discipline from a broad array of scientists.

“I get asked all the time what the difference is between chemical biology and biological chemistry,” says Laura Howe, the academic program manager for the University of Michigan’s Program in Chemical Biology. “It’s a very familiar question.”

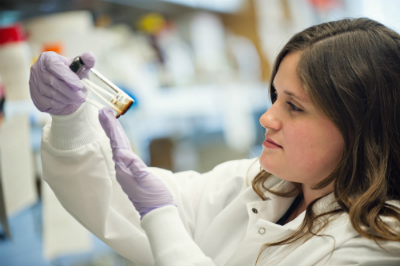

At its core, chemical biology applies the tools and techniques of modern chemistry to answering biological questions that have resisted traditional approaches. For example, to better understand the interactions in a signaling pathway that often becomes defective in cancer, doctoral student Omari Baruti works with proteins that have been chemically modified to lock onto otherwise-transitory partners when ultraviolet light is shined on them.

“When people ask, I tell them biochemistry tries to understand the chemistry that’s involved in a biological process, while chemical biology is more about the tools you use to study a biological problem,” says Baruti.

And even as the emergent discipline lays claim to the exciting border territory between the well-established fields of chemistry and biology, graduate programs like the one at the U-M are dissolving some institutional boundaries as well.

Michigan had long established research strengths that fall under the umbrella of chemical biology, but they involved small pockets of faculty tucked away in different units — biological chemistry, biophysics, medicinal chemistry, organic chemistry, pharmacology — explains program director Anna Mapp, Ph.D., a faculty member in the Life Sciences Institute, where her lab is located, and in the Department of Chemistry in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

"Each department had its own guidelines, which made it difficult for students with interdisciplinary interests to get the training they needed,” Mapp says.

The U-M’s Program in Chemical Biology, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary, in essence established a campus-spanning, virtual department that now unites 46 faculty from 10 departments across the Medical School, College of Pharmacy and LSA — while also providing a core curriculum and additional programming for its students.

University President Mark Schlissel has frequently stressed the strength that comes not just from the U-M’s depth in specific areas, but from the scope of its intellectual diversity as well.

“I’d like to invest in and promote academic programs that really tap into the breadth of the university,” Schlissel told The Ann Arbor News in an interview about his top priorities. “The great problems and challenges that society faces, they don’t know what discipline is supposed to study them — they’re just problems.”

Carol Fierke, Ph.D., a chemist who helped launch the U-M’s chemical biology program and who is now dean of the Rackham Graduate School, says the program creates precisely this type of synergy. “The chemical biology program is a great example of where this was done — pulling together faculty from these different schools has created something that’s much more than the sum of the individual parts.”

In many ways, chemical biology’s fuzzy boundaries have been a boon, Mapp adds.

Chemical biology “means different things to different people,” she and her colleagues wrote in one of the first issues of ACS Chemical Biology in 2006. “Rather than trying to impose a specific vision of what chemical biology should be, we have taken a very open attitude. The chemical biology doctoral program at Michigan is structured to maximize the flexibility a student has in designing his or her curriculum and to place the key decision points in the hands of the students.”

This student-centered focus was a big attraction for doctoral student Lyanne Gomez-Rodriguez.

“It’s very pro-student,” says Gomez-Rodriguez, whose research in LSI faculty member David H. Sherman’s lab centers on using natural compounds produced by marine microorganisms to try to inhibit an immune system-thwarting protein made by HIV. “It’s not competitive. Everyone really wants you to succeed — which, from the stories I’ve heard from friends in programs at other universities, is not always the case.”

During the visitation weekend for prospective students, she was impressed by the stress on interdisciplinary collaboration. “Every professor that I talked to would say, I have this collaboration over here and another collaboration over there,” she says. “And in their labs there was a sense that everyone wanted to help each other — that’s definitely not what I experienced back home in Puerto Rico.”

Baruti, who is working on projects with mentors both in the chemistry department and at the LSI, says the welcoming environment also won him over.

“When new students first come, there’s a whole orientation — the third year students give talks, faculty members present posters about the work in their lab,” he says. “There are regular lunches, too, for first- and second-year students that help you connect with other students. And there’s support, so you don’t have to teach your first year and can focus on your classwork and figuring out which lab you want to join,” he says.

None of these features is an accident, Dean Fierke notes.

“While Michigan is a place where it’s easy for faculty to collaborate, developing a cross-college program is extremely challenging. [Program founder] Gary Glick and Anna deserve a lot of credit for developing the program — working through funding issues, recruiting faculty to participate, adding an extremely successful master’s program in cancer chemical biology — and making it an incredible, nationally recognized program.”

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of LSI Magazine.